Author: Jamie Atkinson (University of East Anglia undergraduate student)

Homelessness seems so inconceivable to many, an impossible and dreadful prospect for most. As one of the world’s wealthiest nations, it is almost expected that we are immune from such a devastating fate. However, a vast 280,000 people are homeless in England, accounting for 1 in every 200 people [1]. Maybe homelessness is something we should think more pensively about, and certainly the government should take more seriously, for homelessness is wide-stretching and causes sweeping devastation.

There are two matters at hand: firstly, why is homelessness so impactful both directly and indirectly, and secondly why does it appear the government and other agencies have abandoned attempts to curb this crisis? Let us not forget that our domestic homeless population is rising every day, and this does not just diagnose our nation as unequal, but in fact as having serious poverty, in this supposed modern and developed world.

Homelessness is not inconsequential.

It is this point which will be touched on first. Whilst it is appreciated widely that there are many direct effects to those who are homeless, effects which are deeply tragic, there are many, if not more, indirect effects from an uncontrolled homeless population. Needless to say, those who are homeless bear a huge number of direct effects such as mental health strains and physical health problems as well as socio-economic concerns on top of these. Evidently, effects such as these are bad enough that we should all want to – and therefore make it a priority to – eradicate homelessness in this country. However, there are also vast indirect effects which spill over, known in economic terms, as externalities. There is enormous collateral damage! For example, the strain that is placed on public services such as the ambulance service and the police is enormous. Demand from homeless people is disproportionately larger for these types of services because they are more susceptible to health problems as well as encounter other problems in society, such as crime related issues. There is therefore said to be a serious overlap [2] between homelessness and social issues, and one can infer further that there is a negative relationship between the number of homeless and the availability of public services. Let us take the police, which the homeless population have a high interaction rate with. Each and every arrest costs on average £1668 [3] and with 7 out of every 10 homeless ex-offenders being re-convicted within one year, it is plain to see the damming effect of abandoning the homeless. Every service is stretched, and the need to reduce demand on these services is ever more present and resolving/reducing homelessness would help this cause.

What is paradoxical is the UK electorate priorities which in a 2018 paper suggest that: 57% of those asked preferred “reducing the pressure on public services” over “ensuring decent affordable housing” [4]. We loosely combine assurances of providing decent affordable houses with homelessness policy because they both aim to reduce those who cannot afford to live somewhere, the crux of the issue. The priorities are paradoxical therefore because if the government were to tackle our housing issue, a proxy for homeless policy, they would in turn be reducing public service pressures as well because there would be less pressure from the homeless. This is the frustrating issue. Agencies and the general public do not see homelessness as something that concerns them, a frankly unsympathetic and wrong standpoint. Homelessness very much does effect each and every one of us because it is a social issue which has an impact on services all of us use. The public perception of homelessness is that it is not their priority, as they cannot see the social links, the supposed overlap or the lasting economic effects that entail. It is this notion which has led to our homeless being forgotten.

Someone needs to break the cycle.

What is so damming about the stories of the homeless is their lack of hope. This stems from the fact that being homeless is self perpetuating: one cannot get money through a job to be housed so is homeless. This means they cannot effectively rejuvenate any career possibilities. It is a vicious cycle! The only way to break this cycle is for the government to intervene, to break these people from the cycle, which will improve their quality of life indefinitely, and in turn deal with the other externalities of homelessness which are inadvertently forgotten about. Intervention is difficult however and is time-consuming and costly. It is very much akin to the poverty trap seen in developmental economic fields because there needs to be a vast push to change the prospects of those living in poverty. The lack of will to make this push has meant the homeless have, up until now, been abandoned.

Take responsibility or pass the buck?

Many would argue that by virtue of the fact there remains a homeless population, the government have passed the buck to a small extent. Emphasis here is on small because the government have done and continue to utilise policy to help homeless people to some extent , though this again has been a small effort. There have been three main pieces of legislation which aim to deal with homelessness:

- Housing Act 1996

- Homelessness Act 2002

- Homelessness Reduction Act 2017

The first two pieces of legislation formed the building blocks for policy in this country, which recognised those in need, especially the vulnerable, and formed the statutory underpinning for action. Both these policies however seemingly placed the responsibility on the local authorities and councils. Currently in place is the Homelessness Reduction Act 2017 which encompasses the previous acts and aims to build on them. Critical to these acts are the notions of early intervention by local authorities and the ‘duty to refer’. This means councils and agencies must refer those at risk of homelessness to the relevant housing bodies, especially those in the most vulnerable categories (such as pregnant women) within 56 days. The action taken on behalf of this act is very much local authority led and although the gross direct cost to government of homelessness is £1 billion [5], the government need to do more themselves to curb the crisis. For example, for a long time now there has been a vast issue of affordable housing in this country and so the government needs to put more emphasis on building affordable housing, especially for the young and vulnerable so they do not enter the vicious cycle mentioned above. This would cost billions of pounds more, however what price should we put on putting a roof over someone’s head?

Some argue that such questions are irrelevant because homelessness is a problem for the homeless. It is a ‘self-makingness’ model[6]. This model is a very capitalist model which simply suggests that the human future is decided by one self, ultimately suggesting homelessness is self-made. This has further separated the public from this apparent ‘non-issue’. Equally, the general public only see the highly visible form of rough sleeping in their society (only 1.7% of the homeless population [7]), when in reality, there are vast numbers of people who are struggling. These people are negatively impacted themselves and have impacts on the entirety of our nation and so this issue should be prioritised much more heavily. We should however not begrudge them, because it is us, the holders of power, that have not addressed homelessness and have neglected thousands of our people.

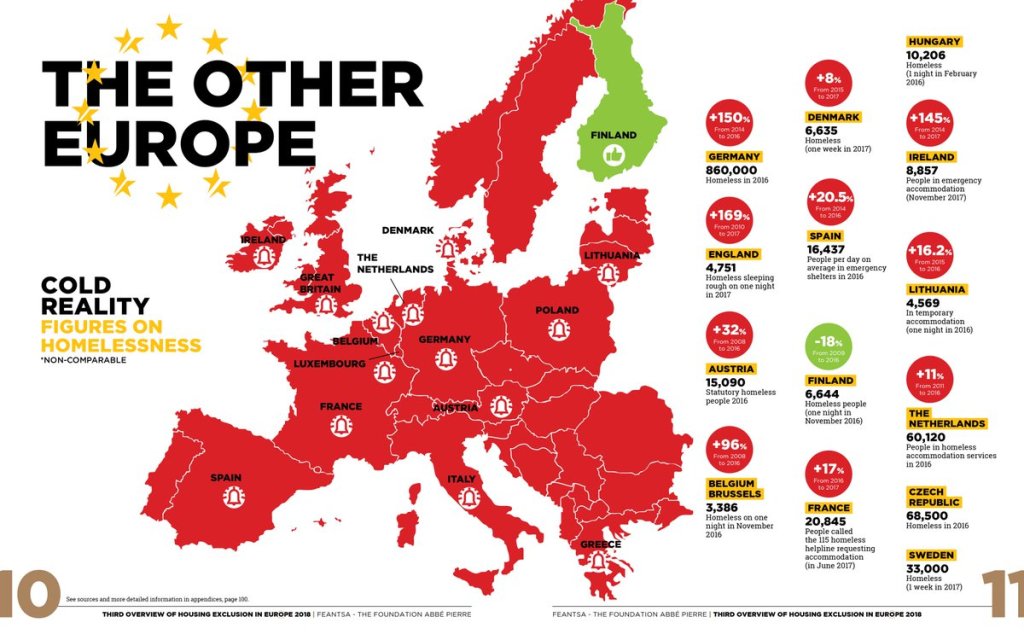

Helsinki, Finland is a good place to look for an effective homelessness tool kit. They have a much reduced homelessness rate and this has been falling for a considerable time now. Their policy ethos is the ‘Housing First Principle’ [8]. Unlike other countries who provide staggered, temporary accommodation variants as the homeless tackle their different problems, Finland provide permanent housing immediately for these people so they have a firm foundation to fix all these respective problems. This permanent housing arrangement provides a good basis for finding a career and job retention for a start so these people can make a good start to their lives. This is the ultimate safety net for homeless people, who frankly need it so they can have a shot at working, living and thriving like the general population. The UK may therefore benefit from such a policy to make the difference which so far has not been made. This could also be said about most other European countries which are battling like the United Kingdom.

Perhaps in this national Coronavirus emergency, questions will be asked as to why specific homeless intervention hasn’t been prioritised, to protect the welfare and well-being of those who are homeless, and to at least give them the opportunity to, following the government advice, “stay home”.

References

[1] Shelter (2019) This is England: A picture of homelessness in 2019, The numbers behind the story, Available at URL: https://england.shelter.org.uk/__data/assets/pdf_file/0009/1883817/This_is_England_A_picture_of_homelessness_in_2019.pdf, Accessed: 05/04/2020

[2] Mcdonagh, T. (2011) Tackling homelessness and exclusion: Understanding complex lives, Available at URL: https://www.homeless.org.uk/sites/default/files/site-attachments/Roundup_2715_Homelessness_aw.pdf, Accessed: 08/04/2020

[3] Homeless Link (2011) Impact of homelessness, Available at URL: https://www.homeless.org.uk/facts/understanding-homelessness/impact-of-homelessness, Accessed: 08/04/2020

[4] Pagel, C., Cooper, C. (2018) Priorities for the UK – detailed survey results, Available at URL: https://ukandeu.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/2018/07/Pagel-Cooper-survey-summary-31-July-2018.pdf, Accessed: 15/04/2020

[5] Department for Communities and Local Government (2012) Evidence review of the costs of homelessness, Available at URL: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/7596/2200485.pdf, Accessed: 16/04/2020

[6] Crisis (2020) Chapter 4: Public attitudes and homelessness, Available at URL: https://www.crisis.org.uk/ending-homelessness/the-plan-to-end-homelessness-full-version/background/chapter-4-public-attitudes-and-homelessness/, Accessed: 16/04/2020

[7] Shelter (2019) This is England: A picture of homelessness in 2019, The numbers behind the story, Available at URL: https://england.shelter.org.uk/__data/assets/pdf_file/0009/1883817/This_is_England_A_picture_of_homelessness_in_2019.pdf, Accessed: 05/04/2020

[8] Henley, J. (2019) ‘It’s a miracle’: Helsinki’s radical solution to homelessness, Available at URL: https://www.theguardian.com/cities/2019/jun/03/its-a-miracle-helsinkis-radical-solution-to-homelessness, Accessed: 25/04/2020

[9] Maria-Josè et. al (2017) Second overview of housing exclusion in Europe, Available at URL: https://ec.europa.eu/futurium/sites/futurium/files/overview_housing_exclusion_2017_en_2.pdf, Accessed: 25/04/2020